The Demographic Timebomb Awaiting Democracies

Singapore announced its new cabinet last week, marking a generational shift in leadership.

Most of the 4th Generation of ministers are in their late 40s and early 50s.

Our Prime Minister, Lawrence Wong, is only 52 years old.

The relative youth of this cabinet strikes me as particularly quirky when viewed against the global political landscape.

In America, the recent presidential transition saw Biden, at 82, hand over the presidency to Trump.

The pattern extends far beyond America's shores.

Modi is 74, Putin is 72, Xi Jinping is 71, Prabowo is 73, and Anwar Ibrahim is 77—all serving as national leaders with no apparent intention of stepping aside anytime soon.

In stark contrast, Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong, who is 73, is already considered a senior figure in Singaporean politics and sees a need to step aside for political renewal.

This perspective shift is remarkable: an age that elsewhere represents the prime of political leadership, Singapore is viewed as the natural time for stepping back from frontline roles.

What emerges is Singapore's almost unique consciousness about age in politics.

The Invisibility Of Demographics in Politics

I have always found it puzzling that very little attention is being given to demography in the media.

This is because demographic problems are largely invisible daily, unlike crises that dominate headlines and our attention.

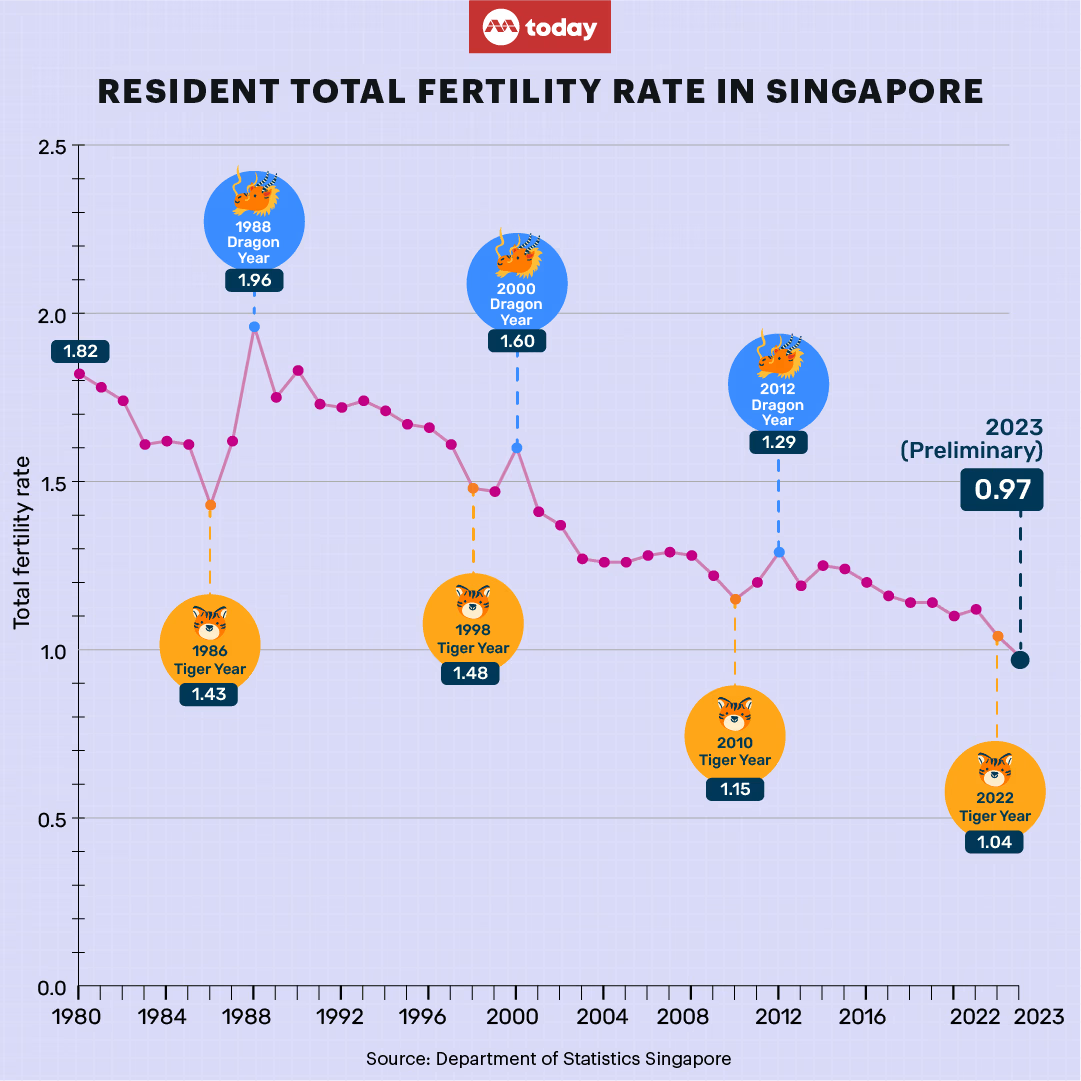

You can feel prices rising, but a dropping total fertility rate has almost no marginal tangible impact on you.

The total number of children you encounter on the street, more or less, feels the same. A TFR of 2.1 or 1.9 is just a reduction of 0.2 on some scale you can’t be bothered to understand.

Ask a guy walking around Orchard Road in Singapore about the economic implications of having 33,541 babies in 2023 vs. 48,635 babies in 1995.

He would probably brush past you.

But even as he walks away from you, the society is reconfiguring itself beneath your nose.

The Economics of Ageing: When China's Dividend Expires

The Great Demographic Reversal

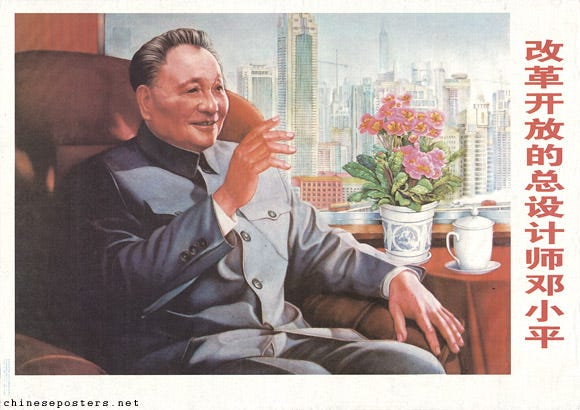

One of history's most consequential economic decisions shaped the world we got used to.

When Deng Xiaoping chose to embed China into the global economy, he didn't just open a market to one billion people—he fundamentally altered the structure of global capitalism.

China's impact was seismic, but not for the reasons most people think.

The real transformation came from hundreds of millions of workers entering the global labour market at extraordinarily cheap wages. Overnight, the world's effective workforce doubled for manufacturing and tradable goods.

Western firms could suddenly offshore production wholesale to factories where labour costs a fraction of domestic wages.

China became the world's factory, churning everything from smartphones to sneakers at prices defying economic gravity. Manufacturing costs plummeted, and the goods filling your home became cheaper year after year.1

There is no way companies like Nike, Walmart and Apple could make supernormal (and obscene) profits without China taking up that role.

This created what economists call the "Great Moderation"—decades of low inflation, falling interest rates, and abundant cheap goods that defined economic life from the 1980s onward.

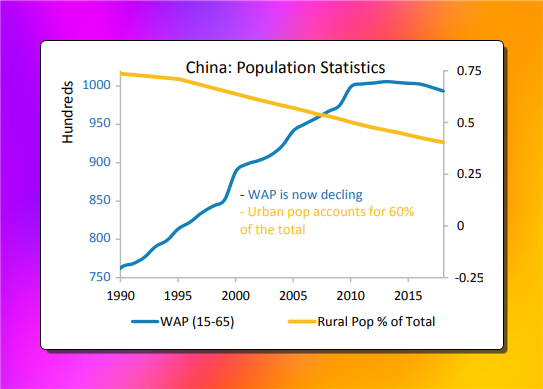

But China's demographic dividend is expiring.2

The country that powered global disinflation is now ageing at an unprecedented rate. China's working-age population peaked in 2015 and is projected to shrink by 200 million over the next three decades.

The factory floors that once absorbed rural migrants are now struggling to find workers.

The magnitude of this demographic reversal has not yet been appreciated and will carry profound economic costs that will reshape our collective economic reality.

The Four Horsemen of Ageing

I summarise Pradhan and Goodhart's four key predictions outlined in their book, The Great Demographic Reversal.3

I must emphasise that the problem compounds dramatically in developed economies that are also ageing.

Whilst China's demographic reversal removes the global disinflationary anchor, local ageing simultaneously increases domestic costs and reduces productivity.

If you are an advanced and ageing economy, you now face the loss of cheap Chinese goods and the mounting expenses of caring for your ageing population.

This double economic squeeze amplifies every challenge.

The Emergence of Chronic Inflation

The disinflationary forces that kept prices stable for decades are reversing simultaneously across multiple fronts. As China's workforce contracts, global manufacturing capacity shrinks, and local workforces in developed nations also decline.

This creates a perfect storm for price pressures.4

Workers who remain in demand gain more leverage and bargaining power.

With fewer people available to fill jobs, wages must rise to attract talent, particularly in labour-intensive sectors like healthcare, construction, and services that cannot be easily automated.

Unlike the 1980s, when an endless supply of Chinese workers kept wage pressures in check, no massive labour pool is waiting to enter the global economy.

Meanwhile, the consumption patterns of ageing societies are inherently inflationary.

Older populations consume more healthcare, personal services, and housing-related services—sectors where productivity gains are limited and costs naturally rise faster than general prices.

Consider this example,

If you are 25, you will buy manufactured goods (such as computers, clothing, and even a car) that may still benefit from technologically induced productivity gains.

Conversely, a 65-year-old who needs hip surgery and home care will unlikely benefit from those gains.

Worsening dependency ratios naturally raise inflation as well.

The larger group of dependents relies on the shrinking working population for consumption, leading to increased demand without a corresponding increase in supply

Economic Growth Slowdown

The same dynamics highlighted above will create a slower growth environment.

As the global workforce contracts, economic output will struggle to expand unless there's an unlikely productivity surge equivalent to China's massive labour mobilisation.

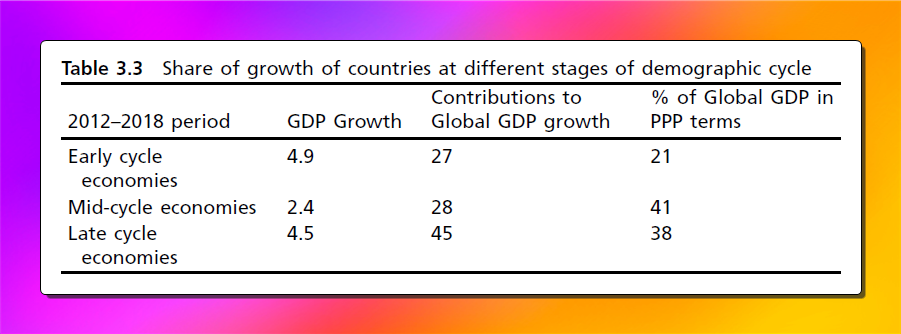

One could argue that technological developments and India/ Africa’s demographic dividend can substitute China’s historic labour mobilisation. Pradhan and Goodhart argue that these other factors can, at best, ameliorate the slowdown.

The End of Low Interest Rates

Ageing societies are reducing their savings rates to fund retirement, just as governments increase spending on healthcare and infrastructure.

More competition for less capital will mean higher corporate borrowing costs, slowing growth.

For severely indebted governments, the debt service costs will explode.

Public Finance Under Siege

Healthcare costs will increase drastically as the economic burden of caring for the elderly rises dramatically.

In particular, as lifespan increases, there will be more people suffering from dementia.5

Of all kinds of care, Pradhan and Goodhart argue that dementia care is perhaps the most expensive.

It is a condition with no cure that requires round-the-clock assistance. Furthermore, dementia care fundamentally requires human supervision and support that can't be replaced by technology.

The fiscal strain will be more severe than most governments anticipate. This means higher taxes, reduced services, or both.

The Political Reckoning

Together, these dynamics represent a fundamental shift away from the economic environment of the past few decades toward a more inflationary, fiscally pressured, and politically contentious future.

Yet, such thinking wouldn’t solve the pressing problems we face.

Goodhart and Pradhan offer potential solutions, but each requires governments to take the bitter pill and implement politically unpopular policies.

Their proposals include:

- Raising retirement ages

- Cutting back on pension funding

- Implementing targeted (but liberal) immigration for care workers

- Shifting from debt to equity financing

- Increasing taxes to fund social spending

- Accepting higher inflation to erode debt burdens.

Despite the pressing demographic challenges, many democracies face three interconnected paradoxes that trap countries in cycles of inaction.

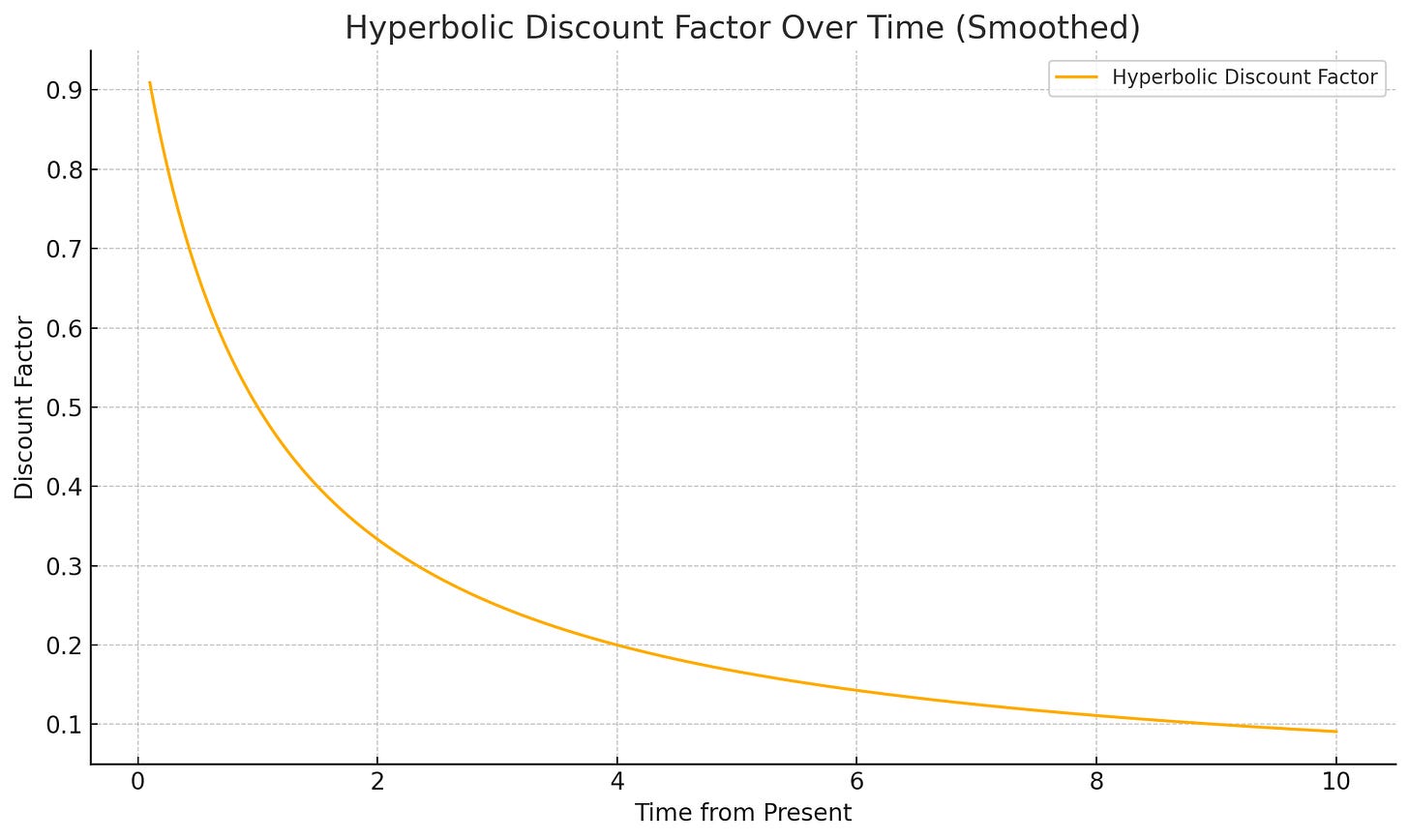

The Hyperbolic Discounting Paradox

Demographic ageing represents perhaps the most urgent and well-documented "wicked problem" of our time, yet many democratic governments consistently fail to address it meaningfully.

This occurs because democracies tend to adopt a form of hyperbolic discounting, systematically underweighting future problems relative to immediate concerns.

The temporal disconnect creates perverse incentives.

Politicians focus on policies that deliver immediate, visible benefits to current voters rather than investing in solutions for future demographic challenges.

Building childcare infrastructure, reforming parental leave policies, or restructuring tax systems to support families requires sustained political will across multiple electoral cycles—a luxury many modern democratic systems rarely afford.

Even when leaders recognise the severity of demographic trends, the political rewards for action remain distant whilst the costs are immediate and tangible.

A government that raises taxes today to fund future pension obligations faces electoral punishment now for a problem that will fully manifest decades later.

The result is systematic procrastination on an existential challenge.

I think this is perhaps most evident in a country like America.

The number of people over 65 in the USA is projected to increase significantly, from 252.1 million in 1990 to 366.6 million in 2040.

Yet, neither Democrats nor Republicans is discussing how to resolve the economic headwinds that this demographic transition will wreak.

PS: President Trump's trade wars should not be dismissed as anomalies—they're early symptoms of this economic transition. As economic growth slows, the fight over existing resources intensifies. The spirit of competition and co-operation ushered in by globalisation in the late 20th century will be replaced by zero-sum thinking.

The Silver Vote Paradox

As populations age, the median voter ages, creating what economists call the "silver vote" phenomenon.

Older voters participate more consistently in elections, have more time to engage with political processes, and represent an increasingly large share of the electorate.

This demographic reality fundamentally alters political incentives.

Parties compete to promise generous pension increases, enhanced healthcare benefits, and protections for existing entitlements.

Meanwhile, policies that might address long-term demographic sustainability, such as immigration reform, family support programmes, or investments in education, struggle to gain political traction because their beneficiaries are either too young to vote or not yet born.

The result is a form of intergenerational resource transfer that operates in reverse, where the smaller cohort of working-age citizens supports an ever-growing population of retirees.

Japan, in this case, is the quintessential silver democracy.

29.3% of Japan’s population is aged 65 and above (as of 2024) — the highest proportion globally. Voter turnout among seniors is consistently high, often exceeding 70%, while turnout among the youth is much lower.

Older voters heavily influence election outcomes, pushing politicians to prioritise pension protection over other long-term reforms.

As Professor Michio Umeda puts it in his report on Japan’s silver democracy,

Politicians in Japan sometimes claim that we should raise taxes (e.g. consumption tax) in order “not to leave a debt to our children (子孫 に借金を残すな)” - At the same time, they rarely claim that we need benefit cuts (e.g. old-age pension) in order “not to leave a debt to our children.” - Why? Because it is politically suicidal!

The Immigration Paradox

Most developed nations facing demographic decline turn to immigration as a potential solution.

Immigrants tend to be younger, more economically active and entrepreneurial, which helps:

- Rebalance the demographic pyramid - expanding the labour force and slowing the rise in dependency ratios

- Increase tax revenues for social security systems without immediately drawing on age-related services like pensions or healthcare.

- Fill Labour Gaps in Care and Services, which locals may shun

- Stimulate economic dynamism through entrepreneurship

Yet here emerges a cruel irony: the countries that need immigration most are often politically allergic to it.

Nations with the steepest demographic cliffs—Japan, South Korea, parts of Eastern Europe—frequently exhibit the strongest resistance to large-scale immigration.

This paradox stems from the same democratic dynamics that create demographic problems in the first place.

Ageing, culturally homogeneous populations often view immigration as threatening social cohesion rather than an economic necessity.

Going back to the earlier example, the same person walking down Orchard Road won’t give a hoot about all these.

But, you know what he will get pissed off about?

Seeing people with thick American, Chinese or Indian accents driving luxury cars, dining out at 3-star Michelin restaurants, while he feels the pinch of a $1 increase on a $5 plate of chicken rice.

The benefits of immigration accrue gradually over decades, while the perceived costs—cultural change, labour market competition, and social tension—feel immediate and personal.

(Hyperbolic discounting again!)

These three paradoxes interlock to create a nearly inescapable trap.

Aging electorates vote for politicians who promise to preserve current benefits whilst kicking demographic costs down the road.

These same voters resist immigration, tax increases, and benefit reforms that could address the underlying problems. Thus, the political system becomes structurally biased toward accelerating the very demographic crisis it needs to solve.

Breaking this cycle would require democratic societies to act against their immediate political incentives—a form of collective self-discipline that few political systems have ever managed to sustain.

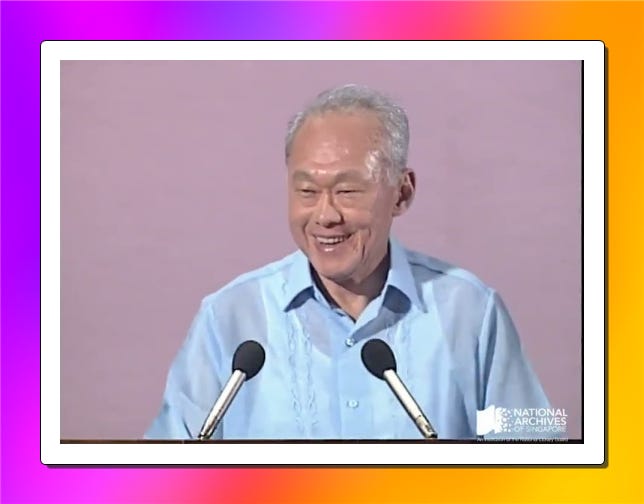

Lee Kuan Yew’s Golden Insight

In 1990, in his final National Day address to the nation as Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew said,

My generation, the old guards, have done what we can for the stability and security on which we built an economy that gives Singaporeans a decent life.

Our final duty is to ensure that we have successors who can continue our work.

We have done this by selecting and testing out a team of some of the ablest and most dedicated of Singaporeans.

They are the best we could find and persuade to take on this responsibility. It has taken nearly 20 years to bring this team together.

The oldest is Ong Teng Cheong, 54 years old (1972 General Elections) and the youngest is George Yeo, 35 years old, (1988 General Elections).

He understood that changing times demanded a disciplined generational renewal at the apex of political leadership.6

Younger political leaders bring three critical advantages in navigating demographic transitions and preventing an inequitable inter-generational transfer:

- They inject fresh ideas with fewer constraints from past policy commitments

- They hold more relevant perspectives on future challenges rather than defending legacy systems

- They understand the stakes for their generation, who will bear the costs of policy inaction

In this context of Singapore’s emphasis on political leadership renewal, we ought to analyse and understand how Singapore is tackling the problems brought forth by an ageing population.

I will focus on this in my next post.

In the meantime, you may check out my interview with Manoj Pradhan, where he elaborates in greater detail on the economic challenges of ageing.

Footnotes:

You might ask what about the East Asian Tigers? We (Singapore, HK, South Korea and Taiwan) rode this wave, but the magnitude of our impact on the world was considerably smaller. I think Keyu Jin puts it best - “China shaped globalization as much as globalization shaped it”.

This book, The Great Demographic Reversal, by Manoj Pradhan and Charles Goodhart, alerted me to the magnitude of the economic challenge of ageing.

I call them the four horsemen because together they can bring about an economic apocalypse in an advanced economy.

Research by Juselius and Takáts demonstrates this clear link between ageing populations and rising long-term inflation. Their research seems to confirm the Lifecycle Hypothesis, which posits that individuals plan their consumption and savings to maintain a stable living standard—borrowing when young, saving during working years, and spending in retirement.

Research by GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators suggest that the number of people living with dementia will triple by 2050 due to ageing populations. (although prevalence will remain the same) The authors cited that globally, the number of people affected by dementia was estimated to have increased by 117% between 1990 and 2016.

Prof Scott Galloway highlighted the downside of having too many old policymakers in a 2022 essay—the central critique is that ‘they have a difficult time understanding new technologies and how society has changed’ and thus fail to develop proper solutions for the present generation. I must emphasise that this leadership renewal is necessary but insufficient.