The Final Days Of Singapore and Malaysia's Separation - Susan Sim

Thank you for checking out The Front Row Podcast and my interview with Susan Sim.

This is the second of a two-part series covering Singapore's merger and seperation from Malaysia.

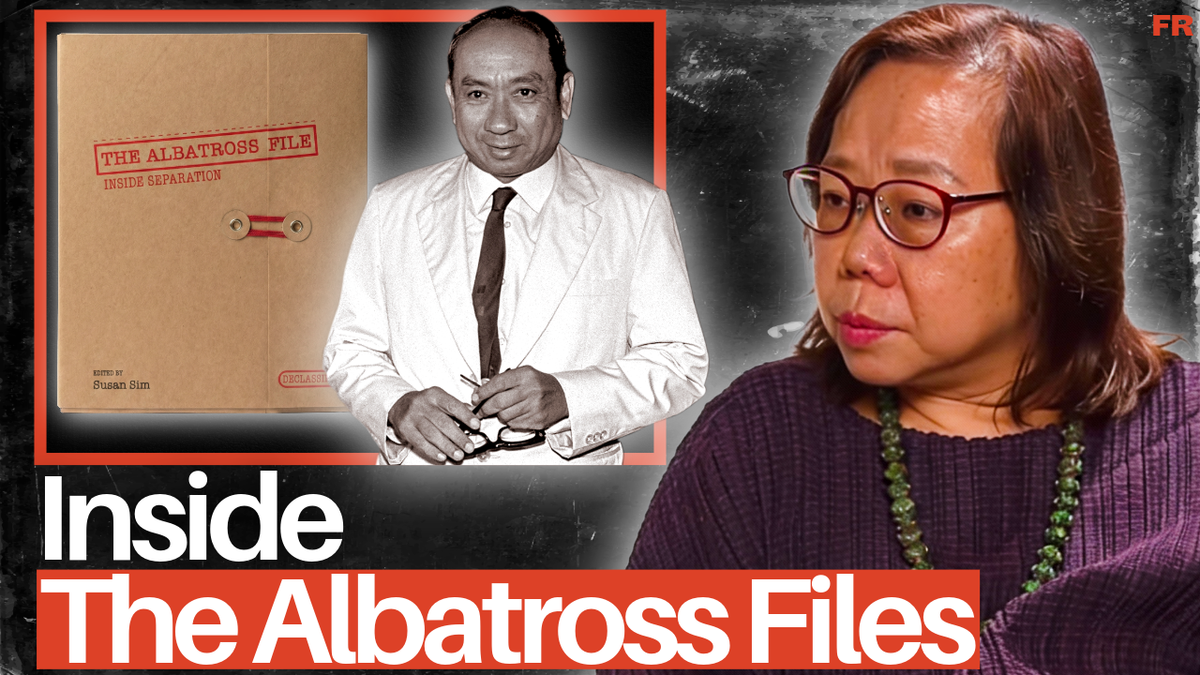

Susan Sim is the editor of The Albatross Files- Inside Separation, a landmark publication that brings to light previously classified documents detailing Singapore's merger with and separation from Malaysia in the 1960s.

For the first time, oral histories, cabinet memos that were previously secret are now declassified. This book brings into light the raw emotions and real struggles Singapore's first generation of leaders faced when contemplating seperation.

She is also the author of The People's Minister, a biography of E.W. Barker, Singapore's longest-serving Law Minister and a key figure in the separation negotiations.

In this conversation, we talk about her editorial approach, the last two months leading up to Separation and why more of us should care about EW Barker.

00:00 Trailer

00:45 What Are The Albatross Files

13:05 Understanding Seperation

28:15 The Emotional Weight of Separation

34:24 Why The Hong Lim Election Mattered

36:50 Why The British Was Excluded

42:43 The Final Week Before Seperation

49:08 The Role of E.W. Barker in the Separation Process

56:38 E.W. Barker: A Man of the People

01:03:07 Lessons for Young Singaporeans from History

Introduction

Keith (00:00:45)

Today I'm joined by Susan Sim. In the last episode, we spoke to Janadas Devan, who brought us through the dynamics of Singapore's merger and separation from Malaysia. Much of our discussion centered around the book The Albatross Files. Today I have the incredible privilege of speaking with Susan Sim, the editor who put the book together. I'm incredibly excited to speak with her about how this book came to be.

Susan, thank you for coming on.

Susan (00:01:18)

Thank you.

What Are The Albatross Files?

Keith (00:01:20)

Before we go further into the secret stories behind it, I'd like to first ask you what the Albatross Files actually are and why they're important for every Singaporean.

Susan (00:01:30)

It's a file that Dr Goh opened probably around mid-1964 when he had one of the first of several meetings over the next few months with Malaysian leaders, especially Tun Razak, who was then Deputy Prime Minister. He would meticulously record those meetings. The first one, he typed up and shared with the cabinet.

Before that, there had already been some concern about the shape the Federation was taking and the impact being part of the Federation was having on Singapore. Lee Kuan Yew, who was then the Prime Minister, had written a memo. It's undated, a cabinet memo, but undated. I think that's how sensitive it was. There were no file registry numbers. I think it was just circulated amongst cabinet members. He talked about the twin evils facing the Federation: racial politics and the communist threat. It was very long, about 18 pages.

This was just before the race riots took place. We think he wrote it before the July 1964 race riots because he doesn't mention them, and something of that magnitude he would have talked about. But it's not in there. We know it's obviously written around mid-July because he talked about meetings he had on 7th July and so on.

Dr Goh obviously kept that memo and then at some point opened a file to put that document in. Over the next 22 to 23 months, he kept some of the memos, drafts of papers intended for the Malaysian Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, and his own notes in this folder.

It wasn't meticulously filed. When I was given access to it, the documents had just been piled one on top of the other. You had to figure out the chronological order.

In essence, the Albatross Files represent Dr Goh's view that by July, clearly after the riots, Singapore being part of the Federation of Malaysia was like an albatross around Singapore's neck. The main aim of going into Malaysia was a common market. Sixty years ago, Singapore wasn't a fishing village. We were more than that. But we were small, didn't have a critical mass yet, and certainly needed a hinterland.

They thought the only way to survive was to be part of Malaysia. When the PAP won the most seats and formed the government in 1959, they campaigned on being part of Malaysia, on merger.

The Tunku, the Malaysian government, the UMNO party, they weren't terribly interested in having Singapore because in Peninsular Malaysia, Malays were in the minority really. If you add up the Chinese, Indians and others, the population of Malays in Malaya itself weren't the majority. UMNO was formed on the basis of Malay dominance essentially.

They weren't keen on having Singapore because Singapore's majority Chinese. If we joined Peninsular Malaysia and formed one country, the Malay population would definitely not be the majority anymore.

But the British government was still responsible for our external defence and foreign policy. They were quite keen for us to be part of Malaysia as well because their concern was that at some point, the communists might take over in Singapore. They didn't want that. They thought if we were part of the Federation of Malaysia, a larger Federation, the chances of that happening were much less.

That's why we went into merger with the Federation of Malaysia. But there was a lot of idealism involved. Singaporeans, what we call Singaporeans now, they thought of themselves as Malayans in those days. That was their identity. This was one nation, never mind that we were part of the Straits Settlement, a crown colony, and not part of the Federation of Malaysia when that was formed.

Our leaders certainly felt they were Malayans. People living in Singapore had family ties, families in Peninsular Malaya. So there was that emotional aspect of it, but also the cool pragmatism that to survive, we needed to be part of a larger common market.

That didn't happen. The minute we went into the federation, suddenly from having self-governance, a lot of the financial matters, economic policymaking, even issuing pioneer status, tax exemptions for foreign investments, those were being controlled from Kuala Lumpur.

It became quite unbearable. And then the race riots happened. Goh Keng Swee kept this file to track the state of discussions as well as the internal discussions the PAP government of Singapore was having about how to deal with it.

Most of these were papers written by Lee Kuan Yew. He would record notes of meetings he'd had with Malaysian leaders or with the British High Commissioner or Australian representatives. Every now and then he would put in his assessment of what he thought was going on, the state of discussion, then suggest how we should move ahead, the strategic thinking.

Goh Keng Swee kept all these documents in this file. When he started negotiations with the Malaysians, with Razak essentially, on separation, he wrote notes by hand and put them in the file as well.

The file disappeared for a while and reappeared in a Ministry of Defence storeroom in 1980 when Goh Keng Swee started being interviewed as part of the oral history programme called Political History of Singapore 1945 to 1965. He was being interviewed in '81, '82 and the interviewer found the Albatross Files in a Ministry of Defence storeroom.

The Narrative of Separation

Keith (00:10:02)

It might be useful to situate where the Albatross Files fit in our understanding of Singaporean history. When we think about separation, one of the things you pointed out in the book and publicly is that for the longest time at the start of Singapore's journey, when Tunku Abdul Rahman articulated the story of separation, it was conceived or portrayed as an ejection. There wasn't really contestation within Singapore against that narrative.

Susan (00:10:38)

Tunku Abdul Rahman wrote a column in 1975 in the Star newspaper of Malaysia where he talked about being in a London hospital, wrecked by shingles, thinking about the pain that Singapore, primarily Lee Kuan Yew, was creating for him. The pain that Lee Kuan Yew was inflicting on him with his speeches up and down the peninsula and his insistence on a Malaysian Malaysia.

He decided then that Singapore is like gangrene. When you have gangrene in the body, you cut it out. I think that started the whole process of separation in the sense that he told his deputy in Kuala Lumpur, go find out how the Singaporeans feel about separation.

When Goh Keng Swee went up to see Razak, Razak said, what should we do? Goh Keng Swee said, we go our separate ways. There was no pushback from Razak. He was surprised, I think, but his parting words to Goh Keng Swee were, could you find out how Lee Kuan Yew feels about this? He agreed. He was outsourcing the job that Tunku had entrusted him with, to find out how the Singaporean leadership, primarily Lee Kuan Yew, felt about separation, about going our separate ways.

Keith (00:12:28)

But this wasn't articulated back then, right? Tunku was making that statement.

Susan (00:12:33)

Tunku did write in his column that he had written a letter to Razak, I think dated 1st July, where he said there may be time to cut Singapore off. Essentially he said, cut Singapore off and please find out whether the Singaporeans agree with it, because he did not want it to be a unilateral decision. He wanted it to be a mutually agreed upon separation.

Keith (00:13:07)

To a certain extent, the common imagination is that Singapore was expelled rather than it being a separation.

Susan (00:13:13)

We couldn't have left Malaysia if the Tunku did not want it to happen. He had to be the first one to decide on it, more or less. On the Singapore side, it wasn't a decision that the government of the day came to readily. It was a very reluctantly reached decision.

There were a lot of constraints, a lot of trade-offs that they had to balance. In the Singapore cabinet itself, there were differing views. Lee Kuan Yew himself was quite conflicted. This was, as you would have heard, an article of faith for the PAP that Singapore had to be part of Malaysia. I think they all believed it when we went in, when there was the battle for merger and we went into Malaysia. It was a happy day for Singapore.

But then the trouble started. There was no common market. And then the riots, where Singapore leaders realised that racial and religious tensions could be weaponised against Singapore. They were trying to find a solution to it. There were discussions with the Malaysians because Tunku said, let's talk about how we can de-escalate tensions, more or less, and how maybe Singapore could have greater autonomy. But that didn't work.

The British did not like the idea. So in the end, everything was stymied. But that in a way also started the ball rolling where people started thinking about what sort of other frameworks we can have apart from a looser federation.

I think Tunku himself decided it's time for Singapore to go back to what it was before merger, let Singapore run itself. Goh Keng Swee was probably amongst the first to come to that decision because he's pragmatic, very decisive. You could say he provides a lesson in strategic clarity in leadership and governance.

Eddie Barker says in his oral history interview 16, 17 years later, that he never understood why we wanted merger in the first place, because what do we have in common with Sabah and Sarawak and so on. But there were valid reasons for merger.

By August, July, August, as Goh Keng Swee says, everyone essentially had enough. They were like, how much more of this can we take? We're being threatened all the time. There was great fear for lives as well. Eddie Barker, every time he went up to KL, once he told his daughter Carla, who was 12 years old, if anything happens to me, and this is on the eve of a trip to Kuala Lumpur, if anything happens to me, you will be looked after. I have a Swiss bank account, put aside some money, mummy knows the number.

The family was looked after. He had four children, they were like six to twelve years old at that point in time. But once the process started, they soldiered on. They went up and negotiated the agreement.

Interpreting the Story of Separation

Keith (00:16:50)

How should one correctly interpret the story of separation?

Susan (00:16:54)

When Lee Kuan Yew wrote part one of his memoirs, The Singapore Story, he laid out the facts. He laid out his role, Goh Keng Swee's role. He even wrote and said that it was only in 1994 that I realised that Goh Keng Swee never discussed any other option but separation with Razak. So it's all out there.

That same year, Albert Lau had written A Moment of Anguish where he quoted declassified diplomatic cables from the British, Australian, New Zealand, the US government. So the basic outlines of the story have always been out there.

I'm not sure what Singaporeans were taught in school because I'm of that generation where history wasn't really taught in school. But I don't think, let's put it this way, immediately after, well, on the day of separation itself, the Tunku, in his speech in parliament and subsequent press conferences said, it was my decision.

Then he gave an account of how separation came about. It started with him making that decision and then the discussions and so on. I think he even gave the impression that the documents themselves were drafted by the Malaysian Attorney General, not by Eddie Barker, the Singapore Minister of Law.

I don't know. One can only speculate, but I would imagine that the Singapore government of the day, there was already, it was emotionally charged moments. There were concerns about unity of the Singapore cabinet because some of the key members like Toh Chin Chye, Rajaratnam and Ong Pang Boon were against the idea of separation.

I think the focus for Singapore from 9th August onwards for the government was about Singapore. How do we build an economy? How do we ensure prosperity for the nation? I think there was possibly a sense, possibly I say, because there are no written accounts, but the sense that things could still go wrong because you could still have people in Singapore who feel that they want to be part of Malaysia and you could still have racial violence.

You want to be forward-looking from that point onwards to focus on ensuring what the ideals of equality, democracy, happiness and prosperity, building the society of Singapore instead of delving into issues that could be polarising.

I asked Albert Lau this question when I was working on the Albatross Files and he said, look, the Singapore government never used the phrase, never said we were ejected or ousted. They always said separate, we were separated. The neutral term separation. Ejected, those are other people's terms.

Keith (00:20:54)

So it's a conscious choice. It was just at the end of the day both parties knew that the fundamental visions of how a country should look like were different. Therefore this was a logical conclusion.

Susan (00:21:07)

I don't know how you can have a grand plan unless the other party is playing ball with you. Actually, I would think that before 9th August, we were kind of in a prisoner's dilemma. You cooperate or you defect, right? That's the classic prisoner's dilemma. If both do this or both do that, but if one cooperates and one doesn't, then you end up in a worse situation.

Keith (00:21:39)

If you enjoy this show, please double-check if you're subscribed. Every subscribe matters and it really helps us to grow this show to serve you. Thank you so much for the support. Now back to the show.

Susan (00:21:49)

I think these were really tense 22, 23 months where it was about survival, not about personal ambition. The key thing is that they showed Singaporeans that you have a government that cannot be cowed, cannot be intimidated, that was only interested in doing what is right for Singaporeans.

The Editorial Process

Keith (00:22:17)

When one looks at this humongous book and looks at the Albatross Files, it might be useful to have a sense of how you edited this volume.

Susan (00:22:31)

The Albatross documents in themselves, in the end we've put 23 of them in the book. They're fascinating reading and very well written as well. But there has to be context because these are 60-year-old documents that had never really seen the light of day, that had barely been read by anybody. Clearly, the original documents were hardly ever touched.

With a book of this nature, I looked for examples, but I also had editing principles that I wanted to set out very clearly from the beginning. It's an exercise in transparency. You're putting out documents for anyone to read. But you have to contextualise them, cross-check information against other sources. In some ways, triangulate across other documents of that period.

In triangulating across the national archives, documents from national archives of several countries, Singapore, the United Kingdom, Australia, these are the main countries where the notes of what was going on in that period were diligently kept. Many of the British and Australian documents have been declassified and are actually freely available online. Hardly anyone reads them because why would you unless you were working on a history project.

But my approach to the Albatross Files was I cannot just be a compiler as an editor. I have to make every document, I'm just talking about Albatross Files documents at this point, to make every document, explain the context of every document, so that if that's the only document you read, if you only read one document in the file, you'll be able to see how it fits into the larger picture.

I wasn't trying to provide one narrative, but there are many different arcs. Separation wasn't just one dramatic rupture. It wasn't just one main arc. There were all these overlapping arcs, overlapping fears. Actually, first of all, overlapping arcs. There were different competing forces, different competing fears as well and constraints.

I would read through each document and then where someone, where it's written, a certain idea or certain individual or certain event is mentioned, I would try to footnote it so that if you're coming to this new, you don't know very much about Singapore history to begin with, you would have the means to not just read what I've written, but also to go and look for the documents themselves.

At some point whilst working on the documents, I went to the National Archives. Our National Archives, the Singapore National Archives, they're amazing. They have a lot of materials, a lot of the declassified documents from the British and Australian archives are available. I found, by pure chance, a file titled File on Special Relations, Special File on Relations between Singapore and Malaysia. Actually the title is Special File on Singapore's Relations with Malaysia.

That was being kept, or that had been kept by the British Deputy High Commissioner based in Singapore. The filing of it was as messy as the Albatross Files because some of the documents didn't really have dates or they were hidden in other parts. You had to read carefully to find the dates. Some of the documents were, do not circulate. There were background papers that were written to try to dissuade Tunku and the Malaysian government from creating a looser federation and so on.

The reference is DO 187/60. So I made sure I put that reference number in the Albatross Files so that if you wanted to read the file yourself, you could. If I cite news media reporting, I would reference largely the Straits Times because you can easily access Straits Times archives through the National Archives, the Singapore National Archives.

The whole idea is opening a file, showing the evidence and annotating the evidence, providing further evidence so that any reader, especially Singaporeans, can make informed decisions for themselves as to what it means and what it means for how we see ourselves now, why we are the way we are, about sovereignty, about identity.

Surprising Discoveries

Keith (00:28:17)

What's one surprising thing you learnt throughout this whole process of editing the Albatross Files?

Susan (00:28:21)

I think what surprised me was how raw the emotions were still. The documents themselves were written largely about 60 years ago. You could feel the anguish, sense of humour too, but also the very strategic thinking that was going on at that point in time where Mr Lee would write a memo or paper to his cabinet colleagues and say, this is how I see things unfolding and this is what we must do. But go away, think about it and send me your views. Tell me what you feel about a looser federation.

At that point, the bulk of the Albatross documents, the first part is about looser federation discussions and papers about looser federation and he asked them for their views. There was strong pushback from Rajaratnam. I'm sure in cabinet meetings there was strong pushback as well from Toh Chin Chye, Ong Pang Boon.

With the oral histories, these were recorded about 17 years after separation in 1982. You can almost feel the emotional weight of the decision-making process. Lee Kuan Yew especially was going through why, what was going on. They're going through the history, how they experienced it.

In a way, I think they were also conscious of the fact that they were recording the history of their participation in pivotal moments of Singapore's history as a nation. They wanted readers of, you can also listen to the audio recordings, readers, listeners, to understand why they made those decisions.

History isn't linear. It's not bloodless either. There's a lot of back and forth, and they try to explain it as best as they can, but from their own personal perspective, which is why the book, we have 10 different oral histories, and we try to let evidence decide on the structure.

Organising them, we want to organise them in a way that had a certain coherence to it. We start with Lim Kim San because he's the first person essentially to be told by Tunku that he's thinking of letting Singapore go its own way because he said to Lim Kim San, tell your prime minister the next Commonwealth meeting he can come here as his own prime minister.

Lim Kim San said later that he kind of missed it, what Tunku was trying to say to him and so did not quite report that to Lee Kuan Yew until much later when he reflected on what Tunku meant.

Then it's followed by Lee Khoon Choy because his victory in the Hong Lim by-election of July 10th, 1965 was quite pivotal in showing how much support the PAP still had in Singapore itself.

Then we have Othman Wok who talked because he was, before merger, he was a deputy editor for Utusan Melayu, which had been started by our founding president, our first independence president, Yusof Ishak, but then had, at some point, there was selling shares, UMNO members essentially bought the majority shares. So they obtained control over the newspaper and moved the headquarters to Kuala Lumpur.

Othman Wok was there working as deputy editor. He was invited to meetings with UMNO leaders and he's sitting there listening to them talk about Singapore, Singaporeans. In his oral history, he talked about the impressions he gleaned.

Then there's Ong Pang Boon who talked about why Singapore contested the April 1964 election and Rajaratnam on why he opposed even a looser federation. Of course Goh Keng Swee, Barker who negotiated, who drafted documents and Lee Kuan Yew.

Then after that, after separation, to give a sense of the state of mind of Lee Kuan Yew with Devan Nair and Kwa Geok Choo, Mrs Lee Kuan Yew. So there's a certain method to the madness.

All of these oral history interviews, you can read them on their own. On their own, they're fascinating. Just that for this book, we only focused on merger, if they talk about that, and separation. But all of them also were asked by the interviewers, so what do you think now about separation, now it's been 17 years, how do you feel about separation?

All of them, I think Mr Lee wasn't asked that question, or anyway in the book, but all of them essentially said, the decision makers themselves said, it's the best thing that happened. Read Rajaratnam's oral history, he basically said, yes, we have spent the last 15, 16, 17 years proving ourselves wrong in thinking that we could only survive as part of Malaysia.

The Hong Lim By-Election

Keith (00:34:25)

We talked about the Hong Lim by-election, which was briefly alluded to. I want you to help me understand the significance of that result of Lee Khoon Choy winning the Hong Lim by-election on 10 July 1965. Why was it such a watershed moment for Singapore?

Susan (00:34:43)

PAP had lost the last two elections for Hong Lim. The by-election was forced by the sudden resignation of a former PAP member who had left the party. PAP leaders believed that the Malaysian federal government, basically UMNO, had orchestrated the resignation of Ong Eng Guan so that there would be a by-election because they wanted to test the grounds. They wanted to see how strong support was for the PAP in Singapore.

Around that time, there was a lot of agitation for Lee Kuan Yew to be arrested. Don't forget, the Hong Lim by-election was July 10th. July 8th, things had come to such a point where leading figures of PAP, Toh Chin Chye, accompanied by Goh Keng Swee, Eddie Barker, and I think Lim Kim San, they had a press conference to essentially say, if you arrest Lee Kuan Yew, you better arrest the rest of us too, because we are going to keep pushing for what he's been asking for, a Malaysian Malaysia. Fair treatment for all races.

That was their way of signalling that we know what we are doing and we are not going to play ball. You can't just remove Lee Kuan Yew and think that Toh Chin Chye or Goh Keng Swee will just take over. That's not going to happen.

So they made that point and then they won the election. There were very clear signals, actually stronger than signals. There were very clear statements. They were basically drawing the red lines to say that if you move against us, it's going to be very difficult for you. Then the victory in Hong Lim showed that we have support. We can do what we say.

The British Role

Keith (00:36:52)

Less than 10 days, right, you already have this discussion of separation. Goh Keng Swee meeting Razak and Ismail in KL and that was already when he was confirming that Lee Kuan Yew was open to secession. At this point in time, EW Barker was already drafting separation agreements. I think on 20th of July they were looking towards the separation happening on 9th of August. They were very clear that the British must not have a whiff of this.

Previously Janadas talked about the fact that the British kind of deconstructed any arrangements or were able to politically cut apart any alternative arrangements. Therefore there was this need to put separation as fait accompli. I wanted to ask you, what was it about the British or what was it about Anthony Head specifically that made it important that they kept this away from the British? What were their considerations?

Susan (00:37:58)

The irony of it was that they liked each other. Lee Kuan Yew and several ministers, they spoke to the British diplomats all the time. A lot of it is really about safeguarding Singapore's interests by making sure that the British government understood what was going on and what the wishes of Singapore leaders hoped would be happening.

They were keeping, and Tunku was doing the same thing with the British, with Australians, same with Singapore, British, Australians, New Zealanders and so on. Americans as well, of course. But the Americans kept a more hands-off approach to this.

I think they knew how good the British were at this game. In some ways, it's a diplomatic game. The British had really shown Singapore leaders by March when the initial discussions for a looser federation broke down, how good they were at changing the Tunku's mind.

Don't forget Tunku, if the British file, the documents, Paul Moss's documents are to be believed. Tunku had actually, at some point in December told Ismail, the Malaysian Home Affairs Minister, that he's thinking of cutting out Singapore, throwing Singapore out. The British panicked and said, no, no, no, that cannot happen.

So they wrote a paper with the intention of essentially frightening the Malaysians into not doing it, by putting up arguments, they call punchlines, that Singapore would become a Cuba at their doorstep, the communists would take over and so on.

They were not just directly giving their paper to the Malaysian government, they used their own British officers who were serving the Malaysian government, especially the then Malaysian Inspector General of Police, Claude Fenner. He was a British police officer who stayed on after Malaysian independence and the Malaysians trusted him. He worked very well with Home Affairs Minister Ismail and he had been asked by Ismail to help him draft documents for discussion in cabinet.

So Fenner used some of the language, some of the punchlines that the British diplomats had come up with and put it in that paper. These were discussed in cabinet.

In any event, the Tunku hadn't quite decided what he wanted with any proposed changes. So then he told Singapore, I want you to hive off, but when he said hive off, he did not mean separation. He meant looser federation.

There was all this back and forth. What was very clear, and you see that from reading the Albatross documents, what was very clear was Singaporeans, Tunku simply didn't want Singapore members of parliament in the Malaysian parliament in Kuala Lumpur, arguing with them on policies and in some ways showing them up. He just didn't want Singapore in parliament, but he wanted Singapore to pay for defence and so on. You cannot have taxation without representation.

So that was a non-starter. Then the British persuaded Tunku that, no, no, of course you must have Singapore. The Singaporeans must be in parliament. So Tunku said, okay. If you read one of the notes of meeting that Lee Kuan Yew wrote, he said, I don't understand. Tunku has changed his mind, now he wants us back in parliament, but he wants to give us greater autonomy. How does that work?

Keith (00:42:01)

There was even talk about sending Lee Kuan Yew to the UN, right, during that period of time?

Susan (00:42:05)

That was a Malaysian thing because the British did not think that was a good idea. Especially after the riots. Because it's like, I think it was an open secret. All the diplomatic missions in Singapore, the foreign missions, more or less, especially the British, the Australians, the Americans, they all came to the conclusion that hardcore extremist elements in UMNO had provoked and instigated the riots, the July 1964 riots. You can't then say Lee Kuan Yew steps down and goes because how would that appear to the Singapore ground? He had support in Singapore.

The Final Days Before Separation

Keith (00:42:44)

3rd of August, you had Goh Keng Swee meeting Razak and Ismail and it's told that the Tunku agrees to separation on two conditions. One is Singapore is to make a military contribution to Malaysia's defence and enter into a defence agreement with Malaysia. And Singapore must not enter into any treaty that counters the proposed defence agreement. What was going through Dr Goh's mind? At this point in time, we're like six days away from separation.

Susan (00:43:16)

He saw his job as keeping the Malaysians on track. Whatever they proposed, he wasn't going to argue with them because when you have separation, Singapore becomes an independent sovereign nation. You cannot be telling a sovereign independent nation what to do. We weren't creating a confederation, we were becoming a separate nation.

So he said, sure, whatever. You want us to have brigades? No, we can't afford it. He was trying to reassure them that we would not pose a threat to Malaysia. Of course we were not going to pose a threat to Malaysia with independence. We didn't really have an army. That came about much later.

I think Goh Keng Swee saw his job as that of getting a separation agreement signed and then passed through parliament. He had to go through in one sitting because otherwise, if stretched out over a few days, three readings of parliament and so on, first of all, the ground was agitated. Hardcore extremist elements who opposed separation like Jafar Albar would be agitating his ground.

So you could have violence, could have riots. The British would stop it. They would work on Tunku to say, no, you cannot do this. We are fighting in Sabah and Sarawak against Indonesian saboteurs because this was confrontation. So things could have fallen apart.

Lee Kuan Yew himself was quite reluctant because if you read his oral history interview, he's on 7th August, he's still thinking he could persuade Tunku that, yes, we may have a separation agreement, but if you want us to be part of Malaysia, but in a looser, as maybe a confederation or a looser federation of some sort, we'll tweak the separation agreement and come up with a new arrangement. He's a lawyer, Eddie Barker's a lawyer. They can easily draft another agreement.

Keith (00:45:31)

In a certain sense Dr Goh was there actually not just to keep the Malaysians on track but also to keep Lee Kuan Yew on track?

Susan (00:45:37)

In some ways, yes. I think they're all clear-sighted enough to realise that the status quo at that point in time could not go on. Life could not go on like that. But I think Goh Keng Swee realised that Lee Kuan Yew would agree to separation. That was the only way forward for Singapore.

I suspect, and I don't know, I'm speculating here, I suspect he just didn't want to clutter the issue. He just wanted to not play prisoner's dilemma, to say that this is the path, this is the only path open to us at this point in time. He made it happen. Lee Kuan Yew reluctantly and with great anguish signed the agreement, persuaded Toh Chin Chye, Rajaratnam to sign the agreement and Toh Chin Chye in turn persuaded Ong Pang Boon to sign the agreement.

Keith (00:46:45)

It was worth noting that throughout the whole negotiations, you will see that actually Lee Kuan Yew is conspicuously absent. If one goes back maybe 30, 40 years ago, before all this was released, you would think the Prime Minister would be much more involved, but he was conspicuously absent.

Susan (00:47:06)

Tunku wasn't involved either. Tunku was in London and in Europe before he flew back on August 5th. Yeah, the flight was delayed coming in. I think everyone in the Singapore government knew how much the Malaysian leaders did not like Lee Kuan Yew.

Goh Keng Swee had written the notes of a meeting in July 1964 where he sort of reported the awful things they were saying, the complaints, what he called the usual bellyaching about Lee Kuan Yew. He had circulated it to the cabinet. So Lee Kuan Yew read it, so they all knew.

I think if Lee Kuan Yew had been present in negotiation, it would have been harder to work it out because then someone might be tempted to say, no, no, we don't agree, we want this. And then we say, no, but you can't do it this way and so on. So it would have taken much longer.

I think tactically, it's much wiser if he was not present. And why would he be negotiating with Tunku's deputy anyway? So it should be his deputy. Goh Keng Swee wasn't deputy prime minister, but he was very close to Lee Kuan Yew. So everyone knew that whatever he said had the backing of Lee Kuan Yew.

But Goh Keng Swee, as you pointed out, was also concerned that Lee Kuan Yew might change his mind. That's why he asked him for a letter of authorisation to discuss all possible options, which in his mind would of course include separation. Because if you can't get confederation or looser federation or greater autonomy, then the only other real option is separation. At the end of the day, that was the only real option. Greater autonomy in a federation really wouldn't have worked.

EW Barker's Instrumental Role

Keith (00:49:09)

We all know what happened on the 9th of August and I think there are a lot of publications that detail that fateful day in the Istana in KL. So we will not go into that much because we all know the moment of anguish and for those who are more interested you can refer to the previous episode we did with Janadas Devan or read the book. Read the book.

I wanted to ask about EW Barker because I think his role is instrumental and you actually wrote his book, The People's Minister, which I thoroughly enjoyed as well. Take me through the role that EW Barker played, especially in the last week when there was this sprint towards separation. What was his role in facilitating separation?

Susan (00:50:10)

He had both tangible and intangible roles. He was well-liked by Malaysian leaders. He had played, I think, hockey with Razak at Raffles College. They all studied in Raffles College before going on to the United Kingdom for tertiary education. So they liked him. They saw him as someone who could be trusted because he had not participated in the April 1964 election. So they inferred from that that he did not agree with the decision.

He wasn't very heavily involved in the Malaysian Solidarity Convention. He was at the first meeting. I mean, there are photographs of him there. But then he's a lawyer, so he was probably brought in to draft agreements or the main press statement or something. But he wasn't someone who had gone around making speeches about politics of the day. He was very much focused on his job in Singapore itself.

But he was good friends. They liked him and they trusted him. By most accounts, very good lawyer. He had drafted the separation agreement.

They were discussing the agreement that he had drafted. But he only went up to Kuala Lumpur on the 6th of August, where they were going to finalise the agreement. So obviously he had to be there.

I think at the last minute, Ismail said, we must have this clause to relieve Malaysia of all the liabilities that we might have assumed for Singapore when it entered into any agreement. Goh Keng Swee said, of course, then we must have a clause to say that we will cooperate economically as much as we can and so on and so forth. So Eddie would draft those clauses and put them in.

With him and Goh Keng Swee there, they were both liked and trusted by Razak and Ismail too, to some extent. The discussions, I think by then there weren't so much negotiations as really how do we come to an agreement. I believe they were quite convivial because at some point as they were waiting for the typing of the documents to be done.

This is pre-personal computer days. So documents were being typed on a typewriter. If you make a mistake, sometimes you have to throw them out. I'm not very sure about Blanco in those days, but they threw them out. You have to type with carbon paper so that there's more than one copy and so on. Maybe they typed them separately, I don't know. But you have to make sure that it's a long, tedious process.

So they were waiting for the typing to be done. According to, I think, Goh Keng Swee's oral history interview, he said, the drinks were passed around and I guess everyone was so relieved. As Goh Keng Swee said, it's like a prisoner being given a reprieve. So there was some happy imbibing.

At the end, when it came to sign the documents, as Eddie Barker said, nobody read it before they signed it. He, because he's a lawyer, wanted to read it and was told by Razak, it's your typist who typed the thing, sign it. What are you so worried about? So he signed it. After that, he went back to Istana House, read it, and to his great relief, saw that no mistakes had been made. Then handed over the documents to Lee Kuan Yew.

Keith (00:54:15)

Yeah, it reads to me that EW Barker was like this lubricant of sorts, right? Like he made it much easier for them to, I won't say like what you said negotiate, but maybe discuss. And then after independence he was still a very strong presence informally between Malaysia and Singapore. Can you talk more about that?

Susan (00:54:38)

Because he knew them personally. He said that, you're sportsmen, we don't stab each other in the back. You don't kick a person when they're down. He believed that strongly. That was his sportsman's ethos. He believed in the same ethos. So he would, and they met on the polo grounds at the Turf Club because he, I think at one point owned a horse or owned half a horse.

In the horse races in those days, it was part of a circuit that went up and down the peninsula and Singapore. So they would meet each other at all these locations. He would, even after, for years after separation, every year for Hari Raya, he would lead a small group of Singapore leaders up. Even after he stepped down, he would go with the newer leaders to act as the friendly face, to get everyone comfortable.

He also had a role to play in those days where we had to negotiate the water agreements as well. So it's very important that the Malaysians had someone in the Singapore team that they felt they trusted. Because there was a lot of suspicion that Singapore is always out for itself and so on. They didn't see as much of that in Eddie Barker.

Obviously, if you are the leader of a country, your first obligation is to your citizens. You look after your people first. But it never hurts to have someone whom they feel they can trust to do the right thing as far as from their definition, rather than from our own national interest.

Keith (00:56:40)

I want to help them find out what comes next.

Susan (00:56:42)

Yes, and I think that was always the intention because you were neighbours. There was always intention to have win-win outcomes. If there's already an underlying layer of suspicion that goes back decades, it's a little bit harder.

The Spirit of EW Barker

Keith (00:56:58)

A modern young Singaporean today thinks about someone like EW Barker, we know he's the Minister of Law. He was the Minister of National Development. He was very involved with the sports scene in Singapore. We can name his portfolio and achievements, but what's the spirit that he represented that Singaporeans today can take inspiration from?

Susan (00:57:23)

Everyone who's met Eddie Barker loved him. They saw him as a man of the people. He was someone who was comfortable standing in a taxi line, waiting for a taxi or going to a hawker centre and drinking beer with friends. He was very comfortable in his own skin. I think people liked that about himself.

All these, he was a minister at the time before social media, before Facebook. He didn't have to take photos of himself in hawker centres and put them on Facebook. People just saw him there and word would spread and they knew that that was the man he was.

But there are many facets to him. Apart from being a national athlete who continued to be strongly involved in sports and lobbying for greater sports facilities for the sporting community, for everyone actually, he was someone who also survived the death railway during World War II. He was sent to work on the railway that the Japanese military was building in Thailand, which we call death railway because a lot of people died working on it.

He survived it, but he always had long-lasting health issues arising from that time there. But it never slowed him down. He never talked about the suffering he underwent or he witnessed. He always took it happy, jovial. But he was also, as Law Minister, if you read the book, someone said to me, he formed the template of a Law Minister in Singapore.

He saw his job as, if this is government policy, how can the law make it happen? But he was also a man of conviction. He did not just say, oh, you want to do this? OK, I'll get it done. He would be, are you sure we want to do this? Because this goes against whatever, whatever. Or maybe there's a better way to do it. Maybe we shouldn't use the law to do it. We should apply moral suasion instead.

Also he was someone who would stand up to even Lee Kuan Yew and argue with him in cabinet. Unfortunately we don't have records for all this because, but you hear about them, he's talked about the debates they've had in cabinet with friends.

When he stepped down, I think one interview he did, but he never gave any, except for one or two, he never gave interviews about his work as a politician, as a Law Minister. He would talk about sports, but never about his work. He was very disciplined as well.

So there are many different facets to the man, and it's such a shame that most Singaporeans, many Singaporeans now don't really know much about him.

Don't forget, he also held like four or five different portfolios over a period of 24 years whilst being a Law Minister throughout those 24 years. But he told an interviewer, Kevin Tan once, Kevin was the only person who actually got an interview with him before his passing. He said, what was the job he enjoyed most? Being Minister for National Development. He liked the fact that he was helping to build homes for Singaporeans.

I was shown this photo of him where he's about to put his hand in, in those days when you choose flats, you have to show up and then there's a lottery system and the minister would then put, they had little balls with your number in a little drum and it'll be rolled and then the minister will stick his hand in and take out a number and he'll read the number. So you chose your flat, the floor, the unit, according to the number that was called.

There are a lot of photos of him doing it and he was beaming away. He just loved the idea of building homes. He wanted to make life better. One day he was being driven down the street and he saw it was raining and he saw kids playing in the rain and he thought, we have all these HDB flats and why instead of building flats all the way to the ground floor, why don't we keep them, we create what we call the void deck. Empty space where when it's raining the kids can play indoors.

Now of course, with older people they can also sit down and play chess or just chat with each other. So that's from him.

Keith (01:02:30)

So it's that spirit of public-mindedness but not to take yourself too seriously as a politician that we can remember him by.

Susan (01:02:49)

That's one way of putting it. He also, Lee Kuan Yew said to him once, you're the last Eurasian. And he said, no, I'm a Singaporean. He was Eurasian, he loved being a Eurasian, but his political identity was that of a Singaporean.

Takeaways for Young Singaporeans

Keith (01:03:08)

Given all that we know today, what you've done with the Albatross Files, what are the right takeaways that a young Singaporean should have with regards to understanding Singapore?

Susan (01:03:21)

If you look at Singapore politics, the phrase that's often used by academics is there's a siege mentality. We always feel under siege. We always harp on our vulnerabilities. A lot of it has to do with how we were founded.

There was a sense of siege. There was a sense of great vulnerability where you have a government that did not have control over its own internal security, where someone could come in and whip up emotions and create riots.

The policies thereafter, the housing policies, I think Lee Kuan Yew said in his memoirs, look, if 80, 90% of the population own their own homes, they're not going to be burning them. They're not going to be setting fire to them and doing tit-for-tat violence.

This idea about keeping racial harmony, how fragile racial, religious harmony could be, that's something that is so ingrained in our pioneer generation. That's why there's been this great need to put in place laws and safeguards. We all wish our society could be different. But at the end of the day, I think most of us still are happy with our life here. Life is good. We don't have to worry about our basic necessities.

A large part of it is due to the fact that we have a system that works. It may not work very well for everyone, that's granted, but it works by and large. It's not just because we had a very present government from day one, but it's also because we had generations of Singaporeans who supported the system and worked to build that system for all of us.

Closing

Keith (01:05:21)

Thank you so much for coming on.

Susan (01:05:24)

Thank you.

Keith (01:05:25)

Thanks for listening to today's episode. If you are watching this on YouTube, please consider subscribing and turning on notifications for whenever new episodes are out. If you're on Spotify or Apple, it would help us greatly if you could leave a five-star review on those platforms. Once again, thank you for tuning in to The Front Row Podcast.