Ambivalent Engagement: The United States and Regional Security in Southeast Asia after the Cold War

I recently interviewed Professor Joseph Liow, the former Dean at the Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

The full interview is already out on my podcast.

I spent some time reading and understanding American engagement in Southeast Asia following the end of the Cold War. And obviously, you can't cover the region in an hour, especially when you spent a non-trivial amount of time reading his book.

Naturally, I thought I would share with you my notes from his book, Ambivalent Engagement.

Keith’s Take

When you think about the American presence in Southeast Asia, you have this feeling of incoherence. What exactly does the US want, and what do the different Southeast Asian states want?

You've got the United States behaving like that rich overseas friend who's constantly oscillating between the extremes of warm affection and cold indifference.

One day, they'll tell you how important you are to them and express their desire to grow closer and spend more time together. Next moment, they are criticising your record on ‘human rights’ and ‘democracy’.

Meanwhile, China is like the biggest neighbour on the street.

Their house is always getting bigger, and they are generous and always offer to help you if you ever need them. They genuinely want to be your friend. But you know that those lunches don’t come free.

When you have ‘neighbourly’ conflicts, they instinctively expect you to compromise and give in to them.

And then you have Southeast Asia, who operate more or less like a neighbourhood WhatsApp chat. The only reason you are in it is because you live in the same neighbourhood and want to get along in peace.

Everyone’s perfectly polite at the table, desperately trying to avoid anything that will upset each other.

But when the occasional dispute spills into the group chat, the group greets it with lukewarm silence.

Everyone likes the rich friend and big neighbour because they often come bearing gifts.

But it's not easy managing their eccentricities.

This vibe drove me to Professor Joseph Liow's 2017 book Ambivalent Engagement: The US and Regional Security in Southeast Asia after the Cold War. Prof Liow’s book traces the evolution of the US Southeast Asian policy from the Clinton to the Obama administration faithfully.

It’s a book designed for policymakers in the US to better understand ASEAN for all its quirks and help them chart a better way to engage the region in the coming years.

The point of these notes was to give you a flavour as to why Southeast Asian states in general did not embrace the US as much as our East Asian neighbours.

America’s Unipolar Moment

After winning the Cold War, America enjoyed a unipolar moment.

This meant that they had overwhelming leverage over the world. It also allowed them to indulge in luxury beliefs that would otherwise be politically deadly for any other country, using human rights and democratic ideals as the basis on which it engages with other countries.

At the same time, following the Cold War, where they emerged as the sole victor - the policy elites truly believed in The End of History- which was foretold by Francis Fukuyama.

The objective was simple: “The preservation of US-led liberal hegemony.”

This meant US primacy in the global economy, military and international institutions.

The logic is straightforward: The United States enjoyed primacy, that primacy was good for America and the world, and that primacy is worth restoring or reinforcing.I was previously quite sceptical of this because I thought to myself, surely, everyone knows no empire lasts forever.

I was previously quite sceptical of this because I thought to myself, surely, everyone knows no empire lasts forever. Even the Tang dynasty of China eventually faded into obscurity. Wasn’t that what history taught us?

If so, necessarily any serious national leader must have that in mind, which is that they as a power might not be at the top of the perch forever.

Intellectually, we all understand that. But, it's hard to internalise that lesson truly.

Many American policymakers cannot imagine a world in which they are second.

In other words, they expect American primacy in perpetuity, even though many of them tacitly acknowledge no empire lasts forever.

Regardless of who the President is, Republican or Democrat, they assume that America will continue to lead the world.

Ah, the paradox.

The challenge of learning from history is that we tend to believe that we are an exception to the historical norm.

Nonetheless, as LKY puts it, even today, America might be troubled, but it's still on top.

How Clinton Changed It All

The problem with winning the Cold War is that domestic politics became increasingly contested.

In a democracy with as many lobbies as the US, they demand greater involvement in foreign policy.

Demands and pressures of domestic lobbies and specific interest groups are growing. Human rights, the environment and humanitarian interests are now active players in the U.S. foreign policy process.

These have complicated U.S. relations with some countries in Asia, and distracted the U.S. from its longer-term strategic interests in engaging Asia. Politics in an election year will confound and obscure these interests even more.

America’s Strategic Incoherence

The reason that Southeast Asia, in general, received less attention and thus generate greater uncertainty here about US commitment can be briefly summarized:

- Geographic distance

- Absence of core American interests directly associated with the region

- Absence of a clear and present threat (at least until recently)

Conversely, if you were to survey where America is most intimately involved in, you will find at least a few of these.

The Vietnamese Hangover

Many of my friends in the US policy circles remark that foreign policy in the US is often bipartisan and not affected by domestic politics.

But every leader in Southeast Asia remembers Vietnam. They know that the “mounting domestic pressure compelled the ignominious U.S. withdrawal, which ushered in more than a decade of neglect and led to Southeast Asia’s rapid slide down the list of American strategic priorities.”

In other words, when American withdrew from Vietnam- it was a sober reality check that one could not depend on the US too much as well.

So even at the height of its power, Southeast Asian states were particularly skeptical about the 'end of history'.

Asian Financial Crisis

This episode began to deepen the distrust Southeast Asian leaders had for the US.

Before AFC, Southeast Asia had been riding high on what everyone called the "Asian economic miracle"—a decade of unprecedented growth that had transformed the region.

Then everything collapsed practically overnight. Currency values plummeted by over 70%, foreign investment fled, and what had been stable governments suddenly found themselves dealing with riots and the threat of regime change.

(One could argue that the corruption, nepotism, and excessively financially liberalised markets were to blame. But remember- these were post hoc justifications- no one, not even the IMF, saw that a crisis of confidence was brewing in the early 90s.)

Here's the thing that stuck in regional leaders' minds: American assistance was "not only slow in coming but also that when it arrived, it came with onerous political demands and expectations."

Washington initially stayed on the sidelines, only jumping in when the crisis threatened to spread to Russia and Brazil—essentially when it became America's problem too.

Even more revealing, when Japan proposed an Asian Monetary Fund (you know, neighbours helping neighbours), America blocked it. The reasoning was that such an institution wouldn't demand sufficient economic reforms.

From a Southeast Asian perspective, this looked like America preferring they suffer more if it meant getting better political leverage later.

What crystallised the trust issue was how Washington used the crisis to advance other agenda items.

As one analyst puts it, there was a widespread view that America was "unsympathetic—perhaps even opportunist, considering how it used the crisis to push its democratisation and human rights agenda even further.”

The optics in some cases were as tasteful as President Trump’s public spat with Zelenskyy.

For example, In Malaysia, US Vice President Al Gore publicly criticised his host, Prime Minister Mahathir at an APEC meeting over political dissent whilst the country was fighting economic collapse.

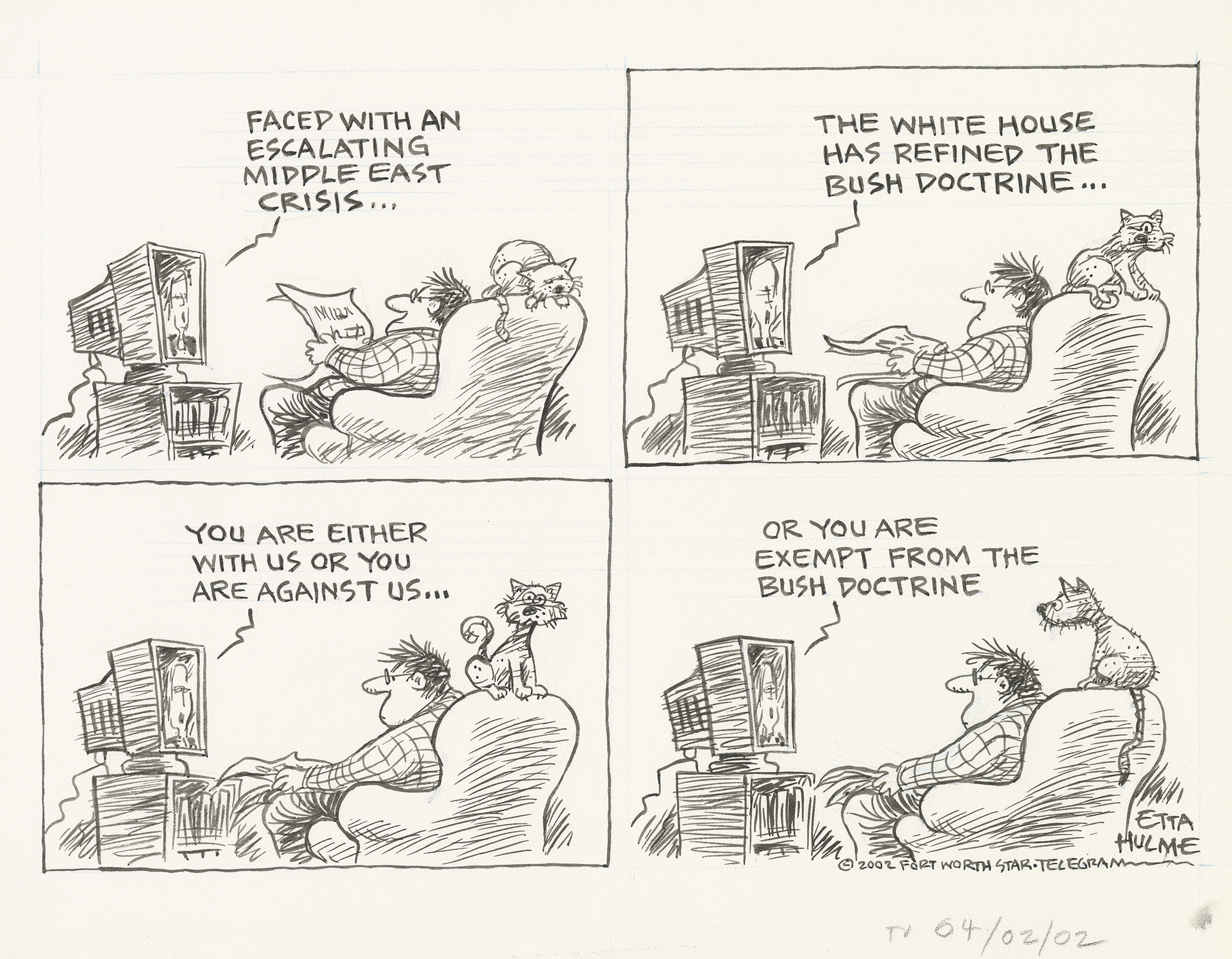

Bush Doctrine

If US exceptionalism coloured the Clinton Admin’s POV - for the Bush admin, it is the war on terror. The 9/11 attacks hardened US resolve to root out terrorism.

Southeast Asia who had problems with this challenge served as the perfect partner as well but the Bush Doctrine only served to make it harder to strengthen America’s relationship with Southeast Asia.

Here’s the summarized or stylized version of it:

1. "You're Either With Us or Against Us"

Bush's Manichean worldview eliminated the comfortable middle ground that most countries preferred. As he told Congress: "Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."

No more neutrality, no more hedging, no more "it's complicated."

Pick a side.

2. Pre-emptive Action

America would strike first based on potential threats, not wait for actual attacks.

As Bush explained at a speech in West Point: "Our security will require all Americans to be forward looking and resolute, to be ready for preemptive action when necessary to defend our liberty and to defend our lives."

Traditional self-defence doctrine said you respond to attacks.

The Bush Doctrine said you prevent them by attacking first. By implication, any partner worth their salt, must in his eyes aggressively take pre-emptive action.

That’s a political impossibility in Southeast Asia - given the overwhelming size of the Muslim population. How is any government going to do this well pre-emptively?

3. Unilateral Action

America would act alone when necessary, regardless of international opinion or law.

This wasn't just about terrorism—Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, refused to ratify the International Criminal Court, and had already pulled out of the Kyoto Protocol before 9/11.

The message: international institutions and treaties are optional when they conflict with American interests.

Here's why this was so problematic for Southeast Asia: these principles directly contradicted the ASEAN way. ASEAN's entire diplomatic philosophy was based on consensus, non-interference, and avoiding binary choices. The Bush Doctrine essentially told them their approach to international relations was now obsolete.

Southeast Asia's Islamic Dilemma

The harsh reality of America's Vietnamese withdrawal showed Southeast Asian leaders they could not rely on America.

The Bush Doctrine alienated them from America.

Yet, many of them could not afford to (because, they needed America)

In a parliament speech, then Foreign Minister, Jayakumar highlighted this uneasy tension:

America’s pre-eminence means that there is no real alternative for any Southeast Asian government than to try to forge good relations with the U.S.

Good relations with the U.S. are not possible unless governments cooperate in the anti-terrorism campaign.

But many Southeast Asian governments will also have to find ways of assuaging the anxieties of their Muslim ground which may be uneasy or unhappy about U.S. policies while at the same time taking firm action to neutralise extremist Islamic elements in their societies.

But how governments deal with this matter is a political conundrum.

How they deal with this will have a profound influence on Southeast Asia now.

Obama’s Pivot East

The Obama administration seemed like a promising fresh change of scenery.

Yet, it turned out it's "Pivot to Asia" ironically typified American strategic incoherence.

Unlike previous administrations that might be excused for regional incoherence due to domestic politics or disinterest, Obama explicitly declared his intention to "deepen US engagement with Southeast Asia through multilateral strategies."

The 2010 National Security Strategy focused on renewing American leadership and preserving American primacy globally, particularly in response to China's rise. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described ASEAN as "the fulcrum of an evolving regional architecture," signalling a genuine strategic commitment.

The most significant implementation failure lay in the administration's excessive emphasis on the "sharp edge of engagement", particularly military presence in the South China Sea.

Whilst the US Navy conducted operations to counteract Chinese expansionism in South China Sea and sought to strengthen defence relations with regional partners, Southeast Asian states sought comprehensive partnership built on the full suite of military, economic, and diplomatic capabilities.

This military-first approach fundamentally misread regional preferences.

The emphasis on security guarantees, whilst addressing legitimate concerns, came at the expense of the softer diplomatic and economic tools that might have built more sustainable relationships.

The policy faced significant obstacles rooted in US domestic politics, which were not lost on Southeast Asian policymakers.

A major illustration was the 2013 congressional gridlock over the federal budget, which precipitated a government shutdown and resulted in the cancellation of President Obama’s scheduled trip to Asia to attend crucial regional summits and bilateral meetings.

(How can you pivot East when you can’t even fly there?)

Even when American policymakers attempted to improve economic relations with the region through the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement) - an attempt to strengthen American investment in Southeast Asia (beyond Singapore) - it failed to gain traction.

Hillary Clinton's abandonment of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement—an initiative she had previously championed—demonstrated how electoral politics could override strategic consistency.

Fundamental Mismatch

The throughline explaining American ambivalence across the different administrations can be boiled down to this:

ASEAN expected the US to be an important strategic economic and development partner, whilst the US prioritised ASEAN as a strategic partner for political and regional security purposes.

This is because the incentives for American involvement has so far been almost tied to either the Cold War or the rise of China as a military power. Beyond that, Southeast Asia as a region serves no intrinsic core American interests.

The notion of a monolithic ASEAN with shared security outlooks is a "chimera".

While generally believing in US involvement, there were "discernible differences" among Southeast Asian states regarding the US's role. States like the Philippines and Singapore supported a strong US presence, while Indonesia preferred a more diversified approach, and countries like Thailand and Cambodia also had complex relationships influenced by domestic politics and historical factors

The Myth of ASEAN Centrality

ASEAN Centrality rests on the belief that ASEAN should be the driver behind “the evolving regional architecture of the Asia Pacific”. (i.e it posits weaker states can function as the "locus of initiative" in regions dominated by great powers.)

Prof Liow highlights that this is a "conceptual anomaly" that is "counterintuitively articulated on the basis of a recognition of weakness rather than strength".

The very foundation of ASEAN Centrality acknowledges Southeast Asian states' limitations, whilst simultaneously claiming they can manage great power competition.

Great powers tolerate ASEAN Centrality not because they truly respect Southeast Asian agency, but because it serves their strategic purposes.

The organisation provides a "neutral platform" for major powers to engage each other on regional issues without appearing to capitulate to rivals. China, the United States, and other powers find it convenient to conduct diplomacy through ASEAN mechanisms precisely because it allows them to pursue their interests whilst maintaining the appearance of multilateral cooperation.

As Prof Liow puts it, "assent is for their own convenience, not due to ASEAN's inherent strength".

For ASEAN policymakers, the lesson here is not to have any illusions that ASEAN is indeed central.

Instead, leaders have to actively strengthen value propositions to both great powers so that their preferences cannot be ignored.

What It Means To Play Both Sides

Few would argue that the U.S. economy would suffer in any existential way should trade, market access, and investment opportunities in Southeast Asia diminish. Likewise, the vast global network of friends and allies the United States has established affords it invaluable access to any number of military facilities. That and the fact that the United States also enjoys long-standing alliance relationships with three states in geographical proximity to Southeast Asia—South Korea, Japan, and Australia—mean it is difficult to make a categorical case that military access to Southeast Asian facilities is, again, vital to core American security interests.

The US enjoys leverage in the region because the truth is, the US doesn’t really need the region. This explains the relative nonchalance they have for Southeast Asia (say compared to EU & NATO)

But, with the rise of China- this calculus has changed.

If the preservation of American primacy and influence globally through the maintenance of its military and economic power and the perpetuation of its values through a liberal international order that it created remains of signal strategic interest to the United States, it stands to reason that this global power and influence is in danger of being undermined by the rise of a presumptive challenger—China.

"American leadership in the region is now being tested, as is the regional order it has underpinned. The region is witnessing at close quarters the rise of China, which, unlike the Soviet Union in a bygone era, is not only emerging as a strategic power of consequence but very much an economic and political one as well.”

This is mimetic desire playing out on a regional level.

As China returns to its historical norm, serving as the primary center of power in the region - the US seeing the rise of its influence, wants the same kind of sway here. This explains why the US (no matter how erratic it can be) - remains interested in the region.

Likewise, no matter how inconsistent the US may be, or how critical policymakers of Southeast Asia are of the US (In the words of our former PM, Lee Hsien Loong)-

“no one in Asia is rooting for an American retreat,” and that if a “secret poll” was taken, “every nation would vote for broader American engagement no matter what they might say in public

Strengthening Our Value Proposition

With all that being said, I asked Prof Liow - in the age of Great Power rivalry, where the operating space is shrinking dramatically and great powers are forcing you to choose sides- what should Singapore strive to do?

This was what he shared with me in our podcast episode together,

I think we need to be able to be sure that our bilateral relationships with the United States and with China are not just on solid ground, but that the value proposition we have for each—unique to each—is of such a magnitude that even if they want to make us choose, they will realize it probably shouldn't be a priority for them in their relationship with Singapore.

This is precisely because they want to ensure that whatever value proposition we can offer them is available to them. This means, of course, that we have to work doubly hard to ensure we have a clear sense of what that value proposition is. For a long time, we've managed to do that, for example, with the United States, in terms of the kind of climate we provide them for investment—not just in Singapore, but through Singapore to the rest of the region. We provide the financial services, the legal and jurisdictional infrastructure for them to be confident that they can indeed reap the benefits of their investments in Southeast Asia.

In the same way, with China, since the 90s, we've always made ourselves available to help China in its own development. Everything from providing executive training for their administrators to the investments we have and the government-to-government collaborations we've initiated, which we will continue to do. So, it's very important that we continue to pay a lot of attention to understand the interests of the United States and China, where they want to see their societies and economies going, and from that vantage, what we can do to help them along. That, I think, will be integral in terms of our relationships with the US and with China.

Recommendations

Prof Liow in his book makes several recommendations.

But his advice to American policymakers to be educated about Southeast Asia resonated with me.

In particular, congressional knowledge and appreciation of Southeast Asia in consonance with American interests must be deepened beyond the constant refrain of human rights.

This can begin with efforts to encourage congressional committee members to travel to Southeast Asia on a more frequent basis in order to provide continuity so as to minimize the deleterious effects of the electoral cycle. The fact that this will be difficult given the political system in which domestic fundraising for reelection appears to be the foremost priority for members of Congress only means that greater effort and coordination must be undertaken by individuals and committees already committed to the region.

U.S. government agencies should also harness the full spectrum of interest in Southeast Asia by way of facilitating regular interactions with other stakeholders from the business, nongovernmental organization, and academic community, perhaps even drawing them into the decisionmaking process. Such collective interactions are critical not only because they both broaden and deepen understanding and appreciation of Southeast Asia,

I would argue that this is advice, we Singaporeans/Southeast Asians can do well to take.

It is also in our interest to better understand the inner workings, political dynamics and national interests of the US (and even, China for that matter).